Month: November 2023

The Gettysburg Address

Sometime after the victory at Gettysburg work began on a national cemetery to give the Union soldiers who died there are proper burial. In October of that year, with about half the work completed, the oversight committee decided to have a commemoration ceremony in November before the weather got too bad. Edward Everett was chosen to be the main speaker. The President was invited to attend and make a few remarks.

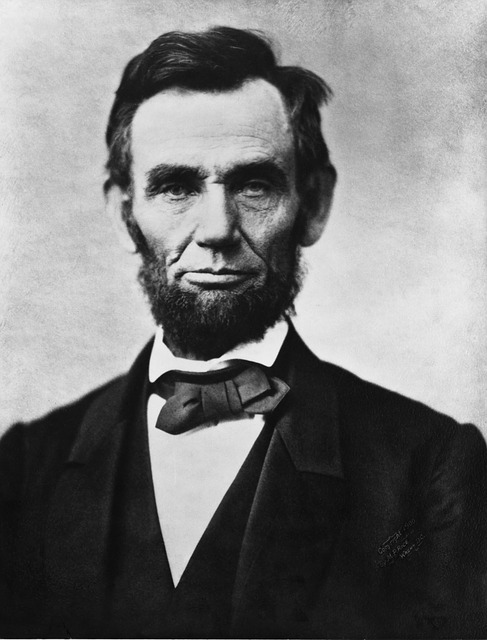

Lincoln left Washington by train on November 18. His retinue included cabinet secretaries Seward, Usher and Blair. Those who accompanied him noted that his complexion was a sickly gray. He looked exceptionally tired and he complained of weakness and headaches. The symptoms were put down to fatigue brought on by the burdens of the war effort. Frustration with the lack of progress had spurred the Commander in Chief to superhuman efforts in his search for a winning strategy.

The Confederate army had won battle after battle in spite of the disadvantages it faced. The Union army had failed to capture Richmond and now it was unable to corral General Lee and defeat him in a decisive battle. General Grant seemed unwilling to take on Bragg’s Army of the Tennessee. Overall, Lincoln’s Army had proven to be expensive but ineffective.

The next day the President stoically endured the ceremony. After Everett’s two-hour oration, Lincoln rose to deliver his comments. A big powerfully built man, he strode boldly to the podium. He studied those attending for several minutes. They likewise appraised him, and judged him to be the rock on which the country’s future could be built. When he broke the silence, he said,

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

On the train ride back to Washington, Lincoln’s condition worsened. Doctors determined that he had a mild case of smallpox.